Unlike the world of Rock music, which would only tolerate the perpetuation of physical youth artificially maintained at the cost of blades and silicon (something the ruthless Otis & Marlena cruelly depicts in Don Juan's Reckless Daughter, 1977).

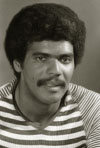

This insight, combined with a genuine curiosity and an artistic temperament, drove Mitchell to explore the wilderness of ethnic sound, where the figure of the "Jazz Black Musician" (a kind of romantic and mystic guru who holds the keys of initiation to Dixieland), and the expressionism of the sensuality of Black Music, seemed to fascinate the Canadian singer. The artistic and sexual freedom exerted by Mitchell, combined with her wonderfully fierce lucidity led to major artistic encounters then. Some virtual, and based purely on a community of thought and goals (for instance with the music of Miles Davis, who always appears at the top of Mitchell's pantheon). Or occurring for real, as with the bassist Charles Mingus, with whom Mitchell at his own request would work. Or again with Herbie Hancock, one of the Jazz scene's most prominent pillar. This cocktail of perspicacity and independence of mind and flesh would also help a few encounters where music and love definitely merge. One thinks especially of Don Alias, a famous superb drummer and a black man, who accompanied the musician in the studio, on stage and also in her life.

It is no wonder, then, why Joni Mitchell (with this delicious spirit of provocation that characterizes most of her artistic acts) would turn up with a black face on the cover of Don Juan's Reckless Daughter. A move inspired by the meeting on the eve of Hallowen on Hollywood Boulevard in Los Angeles, with a black "smooth operator" walking by her in a "diddy bop kind of step" and whistling

Source : Wikipedia

Author: Tom Palumbo 14.01.2008

Source: Creative Commons / Author: Tom Marcello / circa 1976

Source: Wikipedia

Author: Sjaak from

Netherlands

12.12.2006

at her out of admiration while making mischievous comments such as "Hey! Lookin 'good, sistah, lookin' good!". A sunny episode that would urge Joni Mitchell to buy and put on men's clothes and black makeup, appearing at the Halloween party in the guise and outfits of the black sweet-talker. An evening during which none of her relatives recognized her, which made her laugh a lot and have a good time - which was exactly what she aimed for.

Oddly, enlightened minds from academic circles started to examine Mitchell's 1977 joke move, with analytics sometimes questionable, yet often relevant and mind-challenging. However, others invested themselves in a purifying crusade, coming down hard on the musician with absurd assumptions and loathsome accusations of opportunism, racism, and sexism. The main charge being the original sin of indulging knowingly in some "Blackface" odious parody with her "Art Nouveau" persona, consequently insulting the whole Afro-American community .

Even here in Europe in 2015, when I attended the "Court & Spark Symposium" that celebrated Joni Mitchell's career at the University of Lincol in the UK, I was stunned (and sincerely embarrassed for them) to hear some American participants resume a similar witch hunt against the Canadian artist for her "offending" mockery of African American people, while debating on stage and addressing the audience about the singer's "Art Nouveau" fictional character. Yet, when one knows even just a tiny bit about Joni Mitchell’s personality, work, opinions and battles, one can only feel queasy in front of so much bad faith and disinformation. These accusations sounded like nothing but rancid extensions of quibbling clichés brandished by the ayatollahs of the ready-made thinking, whom America has been nurturing and pampering for decades now.

Source photo:

Drummerworld

Photo's Author :

© Martin Cohen

www.congahead.com

Photo: Norman Seeff

Source: Joni

Mitchell’s Site

www.jonimitchell.com

© Jacques Benoit. Design, works, photographies and texts by Jacques Benoit and under the author’s copyright. Except when derived from other sources and then mentioned as such.